Building Your Inner Pause Button: How...

The Hidden Power of a Pause How many times have you wished...

Charles Killick Millard (1870–1952) was a distinguished British physician who earned his MD in 1896 and went on to serve as the Medical Officer of Health for Leicester from 1901 to 1935. [3]

In 1904, Millard published his observations on smallpox and vaccination. Once convinced that vaccination offered complete—albeit temporary—protection against the disease, he found his certainty shaken by the unfolding events in Leicester. The city’s unique approach to controlling outbreaks without compulsory vaccination prompted Millard to rethink long-held assumptions. It marked a profound philosophical shift, compelling him to re-examine the very relationship between vaccination and genuine protection.

...the fact that these prophecies, which were first made nearly twenty years ago, have, as yet, been unfulfilled, is one of the strongest reasons for re-examining the question of the influences of the vaccinal condition of a community in determining small-pox incidence. [4]

After years of direct experience and careful study, Dr. Killick Millard came to challenge one of the prevailing orthodoxies of his time—that unvaccinated people were inevitably at greater risk of contracting smallpox during an epidemic. His observations in Leicester told a different story. Notably, he observed that unvaccinated children were not inherently more susceptible to the disease. In fact, during outbreaks, it was often vaccinated adults who passed the infection to children.

The Danger of Unvaccinated Persons Contracting Small-Pox. — Moreover, the experience of Leicester during the recent epidemic, as in the previous epidemic (1892-93) ten years ago, seems to show that where modern measures are carried out, unvaccinated persons run less risk of contracting small- pox, even in the presence of an epidemic, than is usually supposed. It was predicted that once the disease got amongst the unvaccinated children of Leicester it would “spread like wildfire.” I certainly expected this myself when I first came to Leicester, and it caused me much anxiety all through the epidemic. Yet although, during the ten months the epidemic lasted, 136 children (under fifteen years) were attacked, inflicted largely by once-vaccinated adults, it cannot be said that the disease ever showed any tendency to “catch on” amongst the entirely unvaccinated child population... I have said enough to show that the “Leicester Method” in Leicester succeeded better than was anticipated. [5]

In addition, Dr. Millard challenged the common assumption that vaccination was a wholly harmless procedure. From his years of medical practice in Leicester, he had seen enough to conclude otherwise. He warned that vaccination was not the trivial, risk-free operation it was often portrayed to be, but rather a genuine interference with health—one that, though typically temporary, could at times result in far more serious consequences.

As he put it:

I would say here that from what I have myself seen of vaccination in Leicester, I cannot quite regard it as the trifling operation so many medical men appear to think it. It constitutes a very definite, though usually only temporary, interference with health, and occasionally it is responsible for much more serious ill effects... If it only mitigates, then since the mildest small-pox is admittedly as contagious as the most severe, vaccinated small-pox is no less dangerous to the community than unvaccinated; therefore there is no reason, and therefore no right, to enforce vaccination by law.[6]

Six years later, in 1910, Dr. Millard reached a decisive conclusion: infant vaccination played a far smaller role in controlling smallpox than authorities had long claimed, and unvaccinated individuals did not pose the public danger that was so often asserted. On the contrary, he argued, the greater and less-acknowledged risk came from vaccinated individuals whose mild, “modified” cases frequently went unrecognized, allowing the disease to spread unnoticed. For these reasons, he deemed compulsory vaccination unjustifiable.

He wrote:

Another year has passed without any case of small-pox having occurred in Leicester. It is now four years since the small-pox hospital was last used, or five years if the single case in 1906 be excluded. As I have pointed out before, the experience of Leicester proves that the danger of unvaccinated persons contracting small-pox, even in the presence of an epidemic—provided modern methods of dealing with the disease are efficiently carried out—has been somewhat overrated; whilst the danger of vaccinated persons spreading the disease—through the occurrence of highly modified cases which are so apt to be “missed”—has not hitherto been sufficiently emphasised. It is very doubtful, therefore, whether it is any longer legitimate to justify vaccination being made compulsory, on the ground—at one time so much insisted upon—that “unvaccinated persons are a danger to the community.” [7]

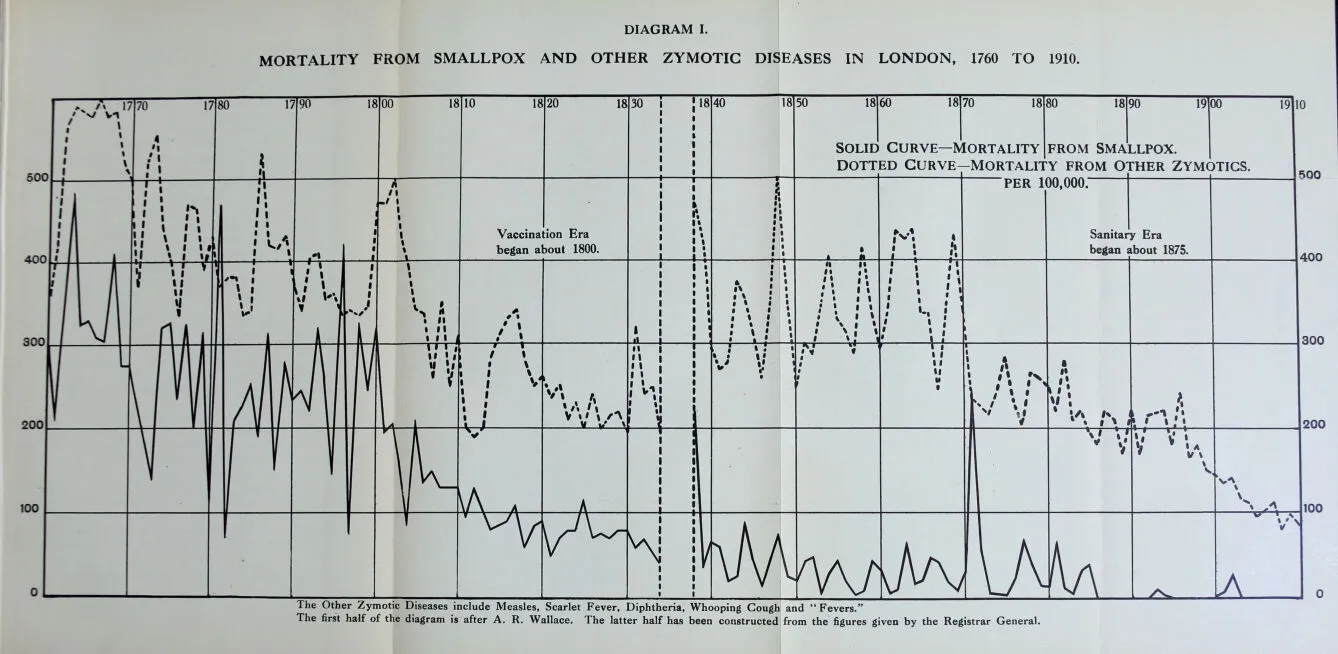

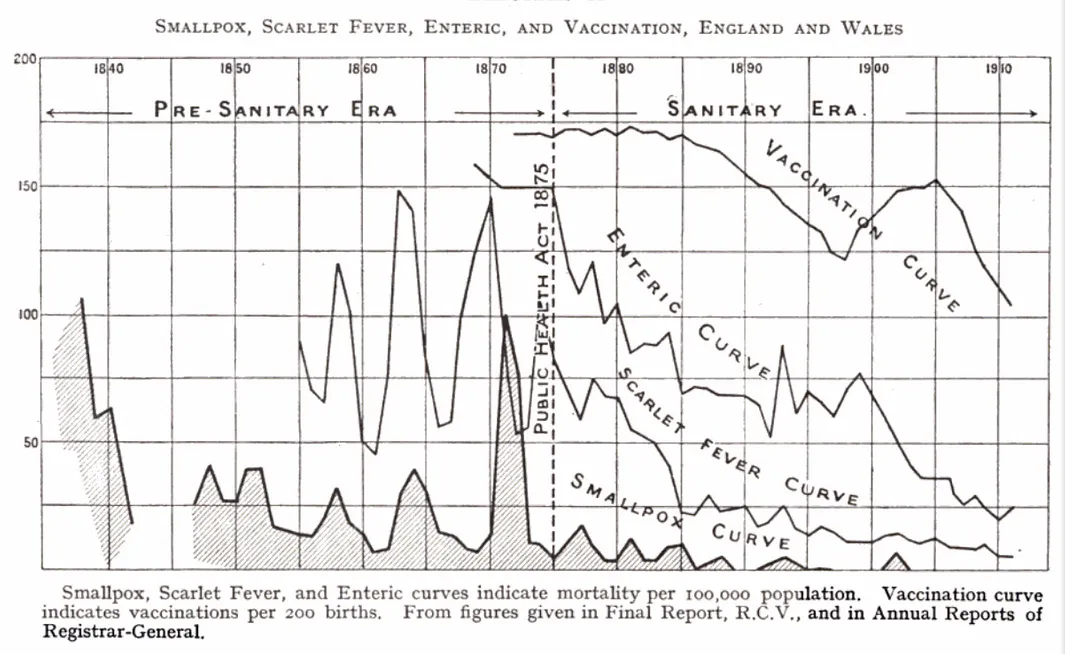

In 1914, Dr. Millard published his landmark work, The Vaccination Question in the Light of Modern Experience: An Appeal for Reconsideration, a direct challenge to the entrenched convictions of the medical profession. In it, he argued—backed by statistical evidence—that vaccination was not the indispensable safeguard it was so often claimed to be. One of the most striking pieces of evidence he presented was charts showing mortality trends in England and Wales.[8] The charts reveal that deaths from “zymotics”—a 19th-century term for infectious diseases caused by microorganisms, such as enteric and scarlet fever—began to decline around the same time, starting in the 1870s.

This decline occurred despite the fact that, among these diseases, only smallpox had an available vaccine. Of particular significance, vaccination rates for smallpox themselves began to drop around 1885 and, by 1910, had fallen by roughly 40% without causing any resurgence of smallpox.

As Millard noted:

Moreover, it will be noticed that the drop in the mortality from “other zymotics” was almost as striking. So much is this the case, that, without being informed, it is difficult to tell which line represents small-pox, and which “other zymotics.” Obviously, causes other than vaccination must have been at work to have produced this fall in “other zymotics,” and we cannot say that the same cause did not also influence the mortality from smallpox. [9]

Forty-two years after his pivotal 1904 report, Dr. Charles Killick Millard looked back and explained why he believed the medical experts of his era had been profoundly mistaken. At the heart of the error, he argued, was a self-reinforcing conviction about the absolute necessity of vaccination.

Looking back it is interesting to consider why medical experts were so mistaken in their prophecies of disaster to come if universal vaccination of infants was abandoned. It was probably due to the belief, then so strongly held, that it was infant vaccination, and that alone, which had brought about the great diminution of smallpox mortality that followed upon an introduction of vaccination. That this was clearly a case of cause and effect was reiterated in every textbook and in every course of lectures on public health. It was hailed, indeed, as the outstanding triumph of preventative medicine. No wonder that medical students accepted it as an incontrovertible scientific fact. [10]

For decades, medical authorities relied on diagrams that appeared to show a tight correlation between the rate of infant vaccination and a decline in smallpox deaths. These visual aids—used in textbooks, lectures, and public health campaigns—seemed to provide simple, undeniable proof that vaccination enforcement was the decisive factor. But, Millard noted, such diagrams were deeply misleading.

We now know that the apparent correlation must have been a coincidence, because smallpox mortality continued to decrease even after vaccination was decreasing also, and this had now gone on for 60 years. Obviously there must have been other causes at work which brought about the dramatic fall in smallpox mortality since the beginning of the nineteenth century, and to the extent vaccination has for so many years been receiving more credit—perhaps much more—than it was entitled to. [11]

Severe state control gradually receded, but only after generations had endured decades of fear and coercion. In the wake of World War II—and the global shock at the atrocities committed under the banner of “public good”—eugenics and other heavy-handed government policies rapidly lost popular support. Their history, once vigorously defended, faded quickly from collective memory.

In England, one of the most visible casualties of this shift was compulsory infant vaccination, which was quietly abolished in 1948—just a few years after the war’s end.

The year 1948 will ever be memorable in the history of vaccination in this country as seeing the end of compulsory vaccination of infants, a measure which has been the subject of such acute and bitter controversy for so many years. Having regard to the great importance attached to universal vaccination of infants as our “first line of defense,” and to the firm belief that only by compulsion could this be secured, it is rather surprising that the proposal to abolish compulsion did not arouse more opposition. In the event the opposition was almost negligible. [12]

For decades, the medical establishment sounded the alarm with a voice both stern and certain. Sir Dominic Corrigan, in 1871, had cast the unvaccinated child as a “bag of gunpowder” [13] — a walking threat destined to ignite an epidemic disaster. Leicester, daring to defy compulsory vaccination, was predicted to crumble beneath the weight of disease, its industries halted, its children lost, and its leaders humbled.

“The plague will stagger the radical authorities,” [14] they warned. Without the “cordon of protected persons,” they claimed, isolation and notification would fail, leaving the city vulnerable and the nation at risk. The battle lines were drawn, the outcome assumed inevitable.

Let them remove the cordon of protected persons about the cases, and their boasted arrangements will prove a delusion; the sick will be without nurses, and the very industry of Leicester will be molested by a plague which will stagger the radical authorities of the borough, and bring the thousands of unvaccinated and unrevaccinated inhabitants to cry for the blessings discovered by Jenner. [15]

The antivaccinators of Leicester... having to a great extent thrown off the armour of vaccination, are waging a desperate and gallant, though misguided, conflict against the enemy... But in Leicester, when its time arrives, we shall not fail to see a repetition of last century’s experiences, and certainly there will afterwards be fewer children left to die from diarrhoea. It is to be hoped that, when the catastrophe does come, the Government will see that its teachings are duly studied and recorded. [16]

But Leicester’s reality proved those fears misplaced. Through steadfast vigilance, prompt isolation, and communal resolve, the city staved off catastrophe for decades. Dr. Killick Millard, who stood at the heart of this quiet revolution, chronicled the truth: unvaccinated children were not the powder keg they were made out to be, and the law forcing vaccination was a blunt instrument that had outlived its justification.

Then came the seismic shock of the Second World War, revealing the dark shadows cast by unchecked state power in the name of “public good.” In the wake of such devastation, compulsion lost its hold. In 1948, England ended compulsory infant vaccination—not with fanfare, but with a quiet, near-unanimous acceptance. The once fiery debate cooled into history, as the world moved on.

The “bag of gunpowder” never exploded. The plague never came. Leicester’s victory was not just over disease, but over dogma, fear, and coercion.

In the long arc of history, Leicester stands as a testament to the power of reason, courage, and community. A reminder that the greatest battles are not always fought with medicine or mandates, but with trust, freedom, and the steady hands of those who dare to resist. If history had truly heeded the experience, logic, and data presented by Dr. Millard, perhaps we would have avoided the path of universal vaccination for every disease—and in doing so, we might have all been healthier, freer, and spared the heavy hand of government tyranny.

1. J. W. Hodge, MD, “How Small-Pox Was Banished from Leicester,” Twentieth Century Magazine, vol. III, no. 16, January 1911, p. 340.

2. “A Demonstration Against Vaccination,” Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, April 16, 1885, p. 380.

3. Killick Millard, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Killick_Millard

4. J. T. Biggs, Leicester: Sanitation Versus Vaccination, 1912, p. 507.

5. J. T. Biggs, Leicester: Sanitation Versus Vaccination, 1912, pp. 510–511.

6. J. T. Biggs, Leicester: Sanitation Versus Vaccination, 1912, pp. 513, 514.

7. J. T. Biggs, Leicester: Sanitation Versus Vaccination, 1912, pp. 406–407.

8. C. Killick Millard, The Vaccination Question in the Light of Modern Experience: An Appeal for Reconsideration, 1914, London, pp. 15–17.

9. C. Killick Millard, The Vaccination Question in the Light of Modern Experience: An Appeal for Reconsideration, 1914, London, pp. 15–17.

10. C. Killick Millard, MD, DSc, “The End of Compulsory Vaccination,” British Medical Journal, December 18, 1948, p. 1074.

11. Ibid.

12. C. Killick Millard, MD, DSc, “The End of Compulsory Vaccination,” British Medical Journal, December 18, 1948, p. 1073.

13. J. W. Hodge, MD, “How Small-Pox Was Banished from Leicester,” Twentieth Century Magazine, vol. III, no. 16, January 1911, p. 340.

14. “Leicester, and Its Immunity from Small-Pox,” The Lancet, June 5, 1886, p. 1091.

15. “Leicester, and Its Immunity from Small-Pox,” The Lancet, June 5, 1886, p. 1091.

16. C. Killick Millard, MD, DSc, “The End of Compulsory Vaccination,” British Medical Journal, December 18, 1948, p. 1073.

Image source: Public domain

Note: The views expressed here do not exclusively represent the views of Materia+ and governing entities.

Check out these recently published articles on Materia+.

The Hidden Power of a Pause How many times have you wished...

The incidence of gluten intolerance, celiac disease and other health problems linked...

A Collective Indictment from Insiders These five declarations, spanning forty-five years from...

Vaccinosis is the term given to those conditions that are a direct...